Teach about Black Artists Series: William H Johnson Art Lesson Black History

William Henry Johnson, one of the great painter/poets of American experience, left South Carolina, the state of his birth, in 1917, when he was only 17, and found a place in the Harlem home of an uncle who made a good living as a porter on the trains that ran north and south. Johnson’s journey was part of the Great Migration, the mass exodus of Black Americans from the South that had begun in earnest that year and that in the years to come would thoroughly transform American society and culture. The double “North/South” consciousness of Black migrants to American cities would become Johnson’s core subject.

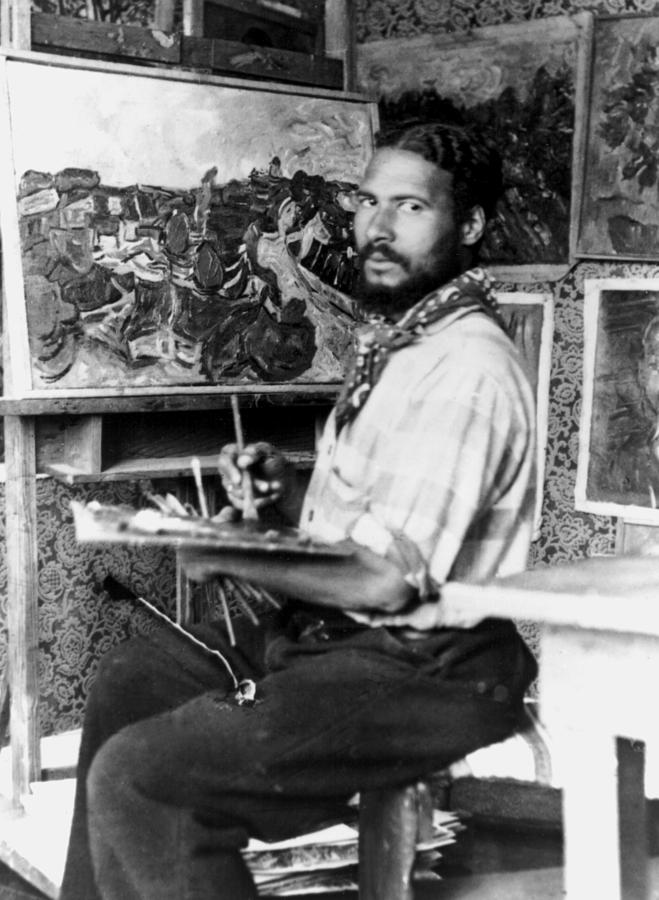

Soon after arriving in New York, Johnson was already able to imagine himself as a professional artist, even with few Black figures as precedents and little formal education of his own. By working as a stevedore, cook, and porter, he saved the money to attend the National Academy of Design, where he excelled to the degree that his teachers raised funds to allow him to study in Europe. There he schooled himself in the lessons of European modernism, using bright colors and loaded brushstrokes to create expressionist landscapes that found small but steady sales. After marrying Holcha Krake, a Danish artist, designer, weaver, and ceramist, in 1930, he spent time in Scandinavia and developed a deep interest in folk art and culture that he carried into his later work.

In the fall of 1938, with Europe on the brink of war, Johnson and Krake returned to New York, settling in Greenwich Village. Their repatriation was prompted by their alarm at the rise of fascism—the previous year, Johnson’s brother-in-law, the Expressionist artist Christoph Voll, had lost his teaching position in Germany and had had his work denigrated in the Nazis’ Entartete Kunst (Degenerate art) exhibition in Munich. Johnson also spoke of a desire to come home to “paint his own people.” In these lean Depression years he found employment, in spring 1939, through the Work Projects Administration (WPA), as an artist/instructor at the Harlem Community Art Center (HCAC), the largest WPA-funded center in the country. There Johnson found himself at the heart of a vibrant community of artists, including Charles Alston, Henry Bannarn, Selma Burke, Gwendolyn Knight, Jacob Lawrence, and others.

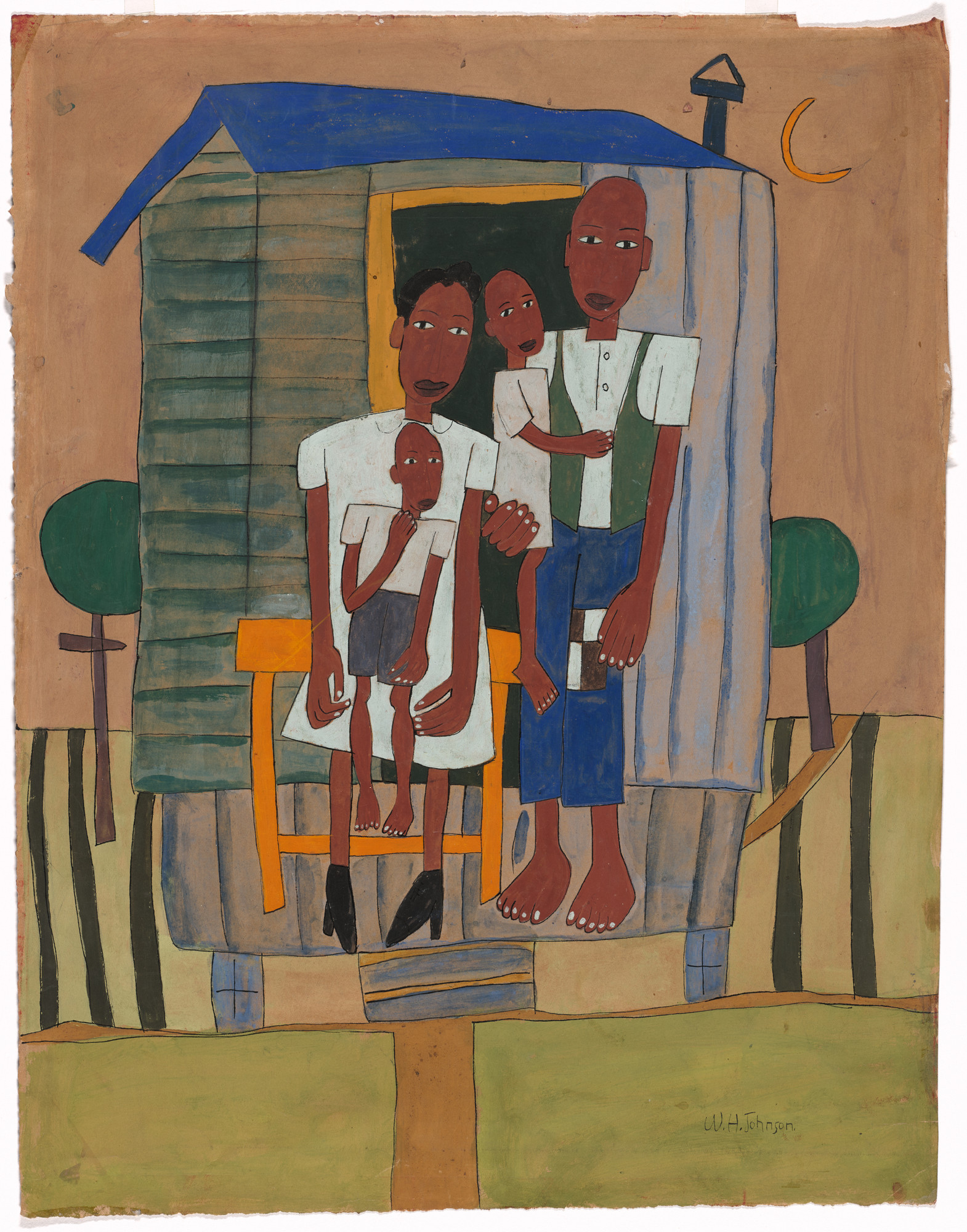

Johnson’s work changed dramatically in New York. He learned screenprinting at the HCAC, where a workshop dedicated to the technique had been set up, and before and after teaching classes at the center he spent time creating hundreds of prints. Screenprinting was generally used for commercial art, but the fine artists at the HCAC were imaginatively repurposing it. The method helped Johnson to define a new visual language of simplified forms and flat planes of bright color laid down in inexpensive opaque inks. It also seems to have served as a prompt for him, allowing him to let go of the painterly expressionist idiom he had honed in Europe in order to embrace something that seemed newer and bolder, that mixed high and low, that could speak plainly of a new kind of urban experience with folk origins. Johnson made prints and paintings in parallel in these years, often tackling a subject virtually simultaneously in both mediums, and the spare forms and vibrant colors that he used in his prints carried over into his painted work too.

In both, Johnson began focusing on images of Black life in the urban North and rural South. Many of his images of this period depict the Harlem community and touch on the forces that made it what it was. The screenprint Blind Singer (c. 1940), for example, pays homage to two street performers. They wear city clothes—suit and tie, hats and heels—but the guitar speaks of the blues, with that music’s deep roots in the South, where it evolved from the songs of Black sharecroppers, and of those earlier enslaved, before making its way to urban areas with the Great Migration.

SOURCE: CLICK HERE

CLICK HERE TO FIND RESOURCES TO HELP YOU TEACH ABOUT BLACK ARTISTS